A wheelchair-friendly pavilion in Dunstable

This steel and glass modernist home in Bedfordshire changed the lives of one couple

Retired racehorse breeder John, 72, planned to build a hi-tech home that would ensure a more comfortable future for himself and his wife Helen, 65, a retired vet who had a stroke in 2018. The couple sold their 17th-century farmhouse to fund a new wheelchair-accessible modernist home on a nearby plot, complete with wildlife garden and self-cleaning swimming pond, with John’s son Ollie as project manager. But dovetailing the sale of one house with the construction of the Grand Designs Dunstable project proved harder than they anticipated.

Kevin McCloud with Helen and John with outside their Grand Designs Dunstable home. Photo: Channel 4

Creating a home for the future

John and Helen had lived in their picturesque 17th-century farmhouse in the Bedfordshire countryside for more than 20 years. The property was in large part devoted to their passion for breeding horses, with 40 acres of land, 19 stables, a training school and several nursery paddocks.

But after Helen’s stroke, which affected her mobility and speech, the house was no longer suitable. Nor was it easily adaptable. So John converted one of the barns and spent his time between the two buildings, carrying her meals across the farmyard on a tray. But they needed a better long-term solution.

In 2019, John spotted a bungalow for sale with a two-acre plot on the outskirts of the village, costing £850,000. The plan was to knock it down and replace it with an accessible new home.

A trained building surveyor, John had collaborated on some residential property developments with his son Ollie, 38, a builder, before. So he felt well-equipped to take on the challenge of creating their own home.

He contacted architect James Arkle of ArkleBoyce to talk through some ideas, and opted for a 440sqm two-bedroom pavilion-style house with a 29sqm annexe housing an additional bedroom.

It’s on a two acre plot set in glorious countryside that John is setting his sights on a brighter future for him and his wife Helen.

See the plans for their fully accessible glass pavilion 🏠 #GrandDesigns pic.twitter.com/3HWdlFKO2F

— granddesigns (@granddesigns) October 5, 2022

A challenging self-build

Work began in autumn 2020 with Ollie as project manager, and an estimate that the project would take 16 months.

The first task was to excavate the basement and build a triple-height, exposed concrete wall. Rising from the basement hall, up the stairwell and into John’s office, the concrete was cast in place using a mould made from Douglas fir planks to create the shape and a textured surface. Though the first few pours went well, the later ones had serious defects and had to be remedied by a concrete specialist, causing delays.

Next came the steel frame and blockwork, followed by the roof and the concrete facias that run around its perimeter. There was an alarming setback when sections of the frame began to snap, causing the roof to drop. The site was closed for six weeks while structural engineers identified the cause of the problem. The steel company repaired the damage and reinforced many of the other joints too.

Floor-to-ceiling windows bring the outdoors in. Photo: Jefferson Smith

Delays and rising costs

Another challenge came when delivery of the windows was delayed, forcing Ollie and the build team to start work on the interior before the house was watertight, which was a huge gamble.

The project was finished in September 2022, overrunning by eight months. This made it impossible to coordinate the sale of the farmhouse with the completion of the build, so Helen and John spent six months living in a rented home.

The final build cost came in at around £1.8m, some £500,000 over-budget, caused by the price of building materials increasing substantially during the project, alongside the delays, additional rent and upgraded fixtures and fittings.

The home is designed to make it easy for Helen to manoeuvre her wheelchair. Photo: Jefferson Smith

Accessible design

Despite all the setbacks, the home has transformed the way Helen and John live. The open-plan living area, an entrance hall and two bedrooms are arranged in a line facing south, with John’s timber-clad office on the first floor above the hall. To the north is a car port and a self-contained apartment, earmarked for a live-in carer should the need arise in the future. The basement gym and wine cellar are reached by a lift or the stairs.

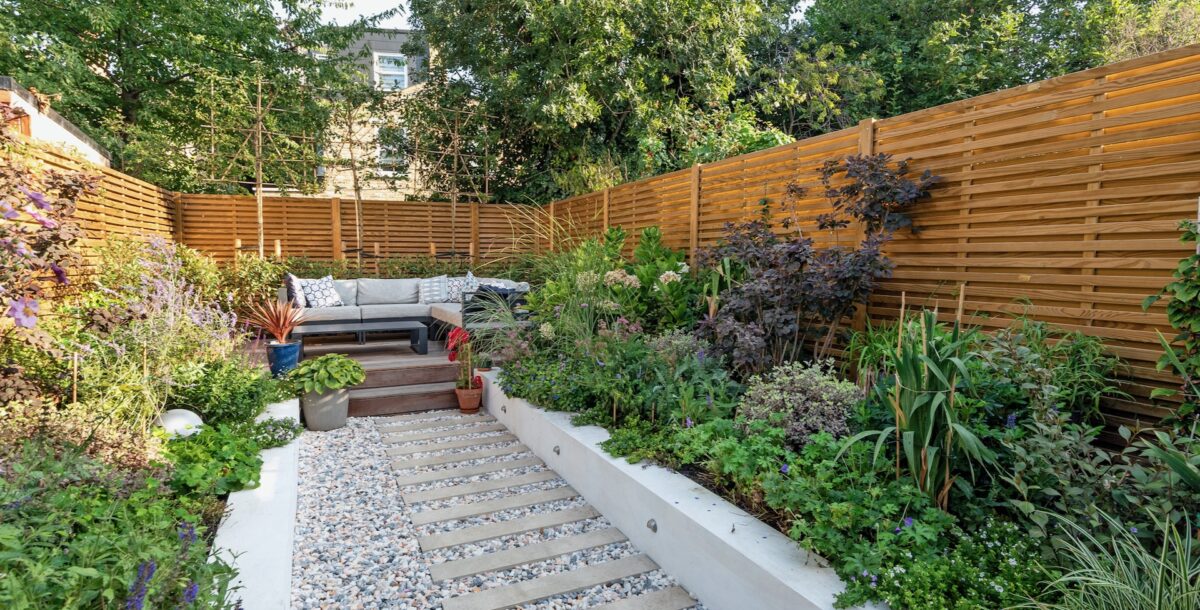

There’s ample space around the furniture, polished concrete floors throughout and step-free thresholds leading out to the garden and outdoor swimming pond, making it easy for Helen to manoeuvre her wheelchair. The kitchen surfaces and appliances are at a lower height than usual, and the generously sized bathrooms include grab rails.

‘From the moment we moved in, the building embraced us,’ said John. ‘It is a real vindication of good architecture.’

Step-free thresholds lead outside throughout the Grand Designs Dunstable home. Photo: Jefferson Smith