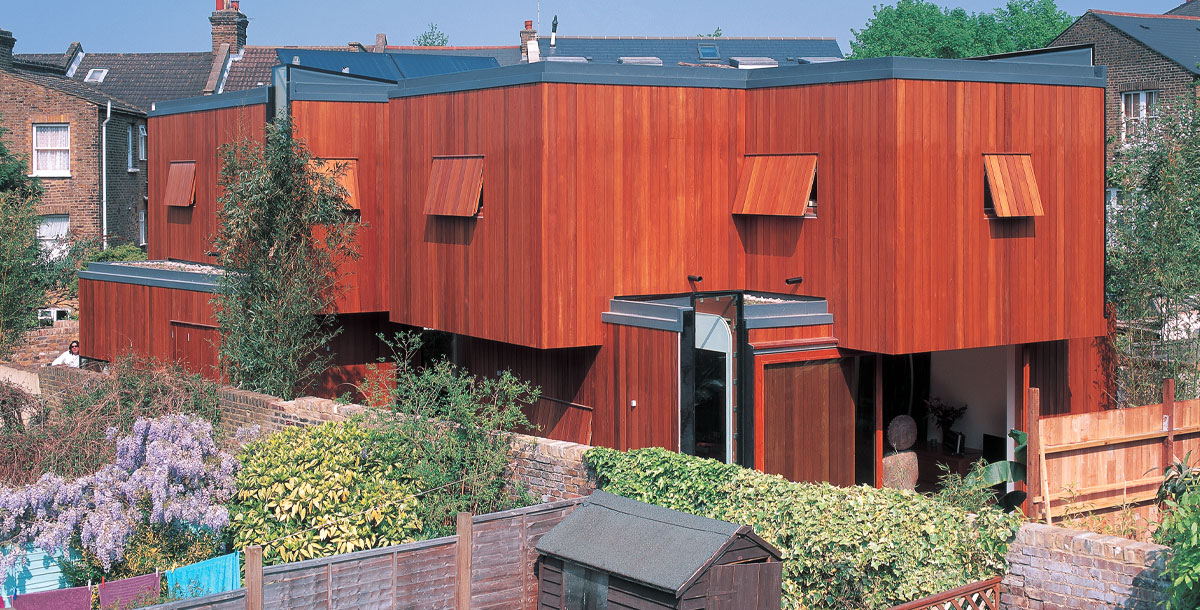

Two eco homes for the price of one in south London

Bill Bradley transformed his carpentry workshop in Dulwich into two eco-homes

Kevin McCloud is not a man given to hyperbole. So when he announced that Bill Bradley’s Grand Designs project in East Dulwich had been ‘driven by precision and rigour… it shows what you can get if you are prepared to pursue quality without compromise,’ you knew he was pretty impressed.

Standing on his plot, joiner Bill Bradley dreamed of incredible architecture and top-notch eco credentials. How did he realise this vision? With faith, graft and unconventional wisdom.

The bespoke panes of toughened glass are thermally efficient in all weathers. Photo: Jefferson Smith

East Dulwich eco houses

Although he didn’t say so directly, you also sensed that Kevin had learned a thing or two from the Australian-born joiner. There was, as Kevin told us several times, virtually nothing conventional about the two glass and timber eco houses (one to pay for the other, leaving him mortgage-free) Bill built on the site that used to house his joinery factory.

Unconventionality also stretched to Bill’s building methods. A man of wood, he approached the houses as if they were a pair of oversized cabinets, laying out a template of them in strips of plywood before he started work on the site.

Then, we saw his carpenters set to work on the buildings’ angled window frames – 28 in total, each a unique size and orientation – before the walls of the house had even been erected. Kevin didn’t exactly doubt Bill’s system, but it’s fair to say it caused him to raise his eyebrows on a few occasions.

The bathroom has a clever secret, the toilet flushes with run off water from the flat roof. Photo: Jefferson Smith

The big sustainable build

Bill, meanwhile, was impressively unflappable throughout the 18-month build. Big delays in the glazing package, un-cooperative weather and soaring costs, nothing seemed to perturb him.

‘We are going for the big sustainable build,’ he said of himself and singer wife Sarah. ‘We are going to create an urban oasis and we want to do it properly. As well as being pleasant places to live, these houses are going to look sensational. We want to prove that green doesn’t mean yuck.’

He certainly proved that. Dubbed the ‘furniture houses’ by Kevin, the beautiful cedar-clad buildings look like a series of precariously stacked, wooden jewellery boxes. A mirror image of each other, the four-bedroom properties are centred around double-height, glazed courtyards with open-plan living areas on each side.

Almost half of the first floor is glazed too, and at ground level large glass doors at both ends of the building open out on to what Bill has rightly called ‘landscaped garden rooms’.

Clever planting creates natural sculptures and decorative touches. Photo: Jefferson Smith

Eco credentials

Topped with sedum (plus branches and stones to encourage nesting) the flat roofs are very green in colour. In addition, the roof’s run-off water drains into a rain-harvesting system the couple use for flushing the toilet and watering the ‘garden rooms’.

Most impressive, the project is green to its very core. The foundations are six-metre steel pins screwed into the ground on a rig – a low-energy system the Victorians used in building seaside piers.

And the houses’ entire structure is made of renewable timber – compressed strands of wood that are as strong as steel, but easier to cut. ‘They also don’t warp, twist, shake or shrink,’ adds Bill.

As well as being energy efficient, the low-impact steel piles also reduced the impact on the plot’s surrounding buildings and walls. This tight, narrow plot is overlooked by no less than 16 houses, not surprisingly, planning permission took two years.

In addition to the glazed courtyards and first-floor walls, it runs from the floor, up to and across the ceilings in the bedrooms and upstairs bathroom. Most important, the glass – sheets of toughened glass fixed to shatterproof laminate – is thermally efficient in all weathers.

The Grand Designs east Dulwich project has a glass and timber exterior. Photo: Jefferson Smith

A few hiccups

Project architect, Martin Williams, of Hampson Williams, wasn’t aggrandising when he told Kevin, ‘we are asking the material to do a lot’. Or when he revealed that each bespoke pane translated into three inches of paperwork.

Bill was certainly sympathetic to the architects’ glassy concerns and, despite an eight-month delay in the glazing package and mounting attendant costs, was, much to Kevin’s occasional disquiet, remarkably unruffled by his long-windowless home. Unruffled, that is, until the day the first pane arrived on site.

Human error is the stuff of life, but it wasn’t a good moment when Bill’s excited team hoisted the 250kg sheet up to its gaping frame and found it was too big. It should have been 1713cm wide, but was 1731cm instead. The last two digits on the order form had been accidentally transposed.

The paint on the walls sucks volatile compounds from the atmosphere. Photo: Jefferson Smith

Building costs

Money was another area over which Bill refused to get agitated. His building costs almost doubled from a substantial £450,000 to a painful £790,000. ‘The rising costs didn’t scare me,’ Bill said after.

‘My only concern was if the land lost value. Our original budget was just unrealistic. It simply became a question of respecting the architecture and not losing sight of our vision.’

That respect ran deep. From Bill’s exquisite soft-opening cabinetry and sliding doors that melt into walls, to his cantilevered floating wood staircase which doesn’t contain a single nail, and which Kevin described as ‘sex without legs’, the internal detailing in this open-plan home is just superb.

Equally impressive, none of it compromises the couple’s green principles: Bill and Sarah’s eco research has indeed proved that green is not yuck. In this instance at least, green has also proved costly: Kevin was visibly shocked when Bill admitted his budget had nearly doubled. All the more gratifying, then, for Bill to respond that an offer for that amount was already on the table for the second house.

The four-bedroom properties have open-plan living areas on each side .Photo: Jefferson Smith

Life after Grand Designs

Since the TV programme, more offers and eco commissions have followed. The Grand Designs east Dulwich project has not just led to mortgage-free living, it has given Bill a new lease of professional life. It really has, to quote Kevin, shown ‘what you get if you are prepared to put your faith in architecture’.

Bill and Sarah’s new home is part of a growing trend. The desire for space is a big issue in the city, and has led to many urbanites applying for planning on back land sites such as gardens and other small pockets of hidden land.

Whitehall has stipulated that 60% of new housing should be on brownfield sites and ‘town cramming’, as the process has become known, takes the pressure off regenerating former industrial brownfield sites.

Interestingly, gardens in urban areas count as brownfield because they are classified as having ‘been residential’. As Bill found, residents’ key objection is overlooking. So, if you are considering building on a small-scale urban plot, hire an architect who has already done so.

Would he do it again?‘ Absolutely. I now have the spec for a green home, where as before I just had a design,’ says Bill ‘Stand by your dream,’ he added.

The Grand Designs east Dulwich project has a central, floating staircase. Photo: Jefferson Smith